(Note: Here’s a review I did way back as commentary editor for pifmagazine.com. It’s since vanished from their archives—Who says the Internet is forever?—so I’ll replant it here.

Prospero’s Books (1991)

Directed by Peter Greenaway

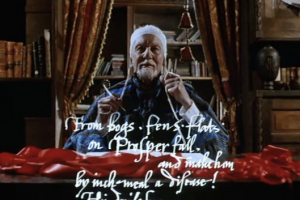

While Much Ado About Nothing and Twelfth Night are worthy of being seen for the curiosity each represents—the former for its unexpected, unprecedented, and unlikely-to-be-repeated synthesis of character, casting and Keanu, and the latter for its unrelenting, clinically precise presentation of pathos in a Shakespearean Comedy—Prospero’s Books, Peter Greenaway’s 1991 adaptation of The Tempest, merits viewing for the simplest of reasons: it is one of the most vigorous adaptations of the Bard ever filmed and easily the most competent and compelling version of The Tempest.

Greenaway is a director whose visual exuberance can overwhelm a viewer. I worked in a small campus theater when his oft-disturbing 1989 film The Cook, the Thief, His Wife, and Her Lover first came out. During its week-long run, I noticed two patterns: people often left in the first fifteen minutes; many of those who remained returned to see the film again the next night. Prospero’s Books is not nearly so graphic, but there are still many reasons a casual viewer might dismiss it. Some may be distracted by such superficial elements as the nudity (virtually all the island spirits are naked—and there are a lot of island spirits) or the fact that, as Prospero, Sir John Gielgud delivers 80% of the lines (speaking most of the lines for the other characters through the first half of the film). Then there are the interpretative elements purists might object to: Caliban’s lines (spoken by Prospero) accompanied by modern dance or a tripartite Ariel. And finally, the second half of the film drags somewhat, particularly when viewed on the small screen, where some scenes lose a degree of their sweep and grandeur.

But those who leave the film half-watched or half-attended have done themselves a marked disservice. The marriage of Greenaway’s always extravagant vision with one of Shakespeare’s most mature plays is a remarkable union. In some of his films, Greenaway’s visual palette can seem forced and overly clever—such as his “one controlling color per room” approach in The Cook… or his “gradually ascending numbers” motif in 1987’s Drowning by Numbers—but in the The Tempest, Greenaway’s wildest whims and most bizarre imagery merely soak into the absorbent metaphoric tapestry of the play, adding to the richness without detracting.

Most simply, the story of The Tempest can be viewed on three levels. One can interpret it literally: a bookish ruler is exiled with his daughter by his usurping brother to a remote island. He commands the spirits to his service and eventually has the opportunity to avenge himself on his brother, choosing reconciliation instead. From a more figurative angle, one can interpret the spirits as figments of Prospero’s imagination (and accordingly ascribe varying degrees of reality and explanation to the remainder of the plot). Perhaps the old boy is just a bit loony. Finally, interpreting as pure metaphor, one can view the entire tale as a look into the mind of the writer/artist and into the artistic process itself. These layers of interpretative space allow Greenaway’s most fantastic images ample room to play. Naked spirits? Well, who can say how such inhuman beings would appear to mortal eyes, even those of a magician? Or in the fancy of a senile or mentally unstable man? And couldn’t these images represent the unclothed and often random ideas that exist in a writer’s mind as he or she creates? One of the most absurd images in a panoply of such images further illustrates the example: During the wedding masque for Ferdinand and Miranda, one of the beings presenting gifts is a hooded, naked man with his feet in two buckets of tar. Say what? Yet such an absurdity resonates with a truth about the writing process: For every honed, well-presented trait or detail put onto paper, how many more random, useless, illogical thoughts, details, and even entire characters present themselves to the author only to be quickly dismissed? How many others, even more absurd, flit along the edges, never even gaining form or recognition?

Having Prospero deliver the majority of the lines could easily be regarded as a gimmick, and indeed some reviewers have professed themselves to be distracted by the visuals to an extent where the language is somewhat lost. I found the opposite to be true. With all the lines being delivered in Gielgud’s distinctive voice, I found myself focused on the language in a way that I had never before achieved through reading or attending productions. Indeed, it is Greenaway’s very patience with the delivery of the lines that can make the film seem overlong (especially to American audiences).

Before Prospero’s Books, Greenaway’s visual excess always seemed on the verge of swamping whatever tale he was telling. With The Tempest, Greenaway finally has a story too expansive to overfill; in return, the Bard’s tale benefits from a potent and original retelling. This should not be viewed as an attempt to present the defining interpretation of The Tempest; it is merely meant to be an interpretation. And for all the visual grandeur and excess and distraction in Greenaway’s vision, it is his respect for Shakespeare’s works and language that shines through most clearly. (Respect, not deference.) Like many of Shakespeare’s greatest plays, a production of The Tempest demands certain things from its director: it demands vigor; it demands imagination; it demands respect. Greenaway meets these demands, and for this, he deserves our thanks.

Film Review: Prospero’s Books

(Note: Here’s a review I did way back as commentary editor for pifmagazine.com. It’s since vanished from their archives—Who says the Internet is forever?—so I’ll replant it here.

Prospero’s Books (1991)

Directed by Peter Greenaway

While Much Ado About Nothing and Twelfth Night are worthy of being seen for the curiosity each represents—the former for its unexpected, unprecedented, and unlikely-to-be-repeated synthesis of character, casting and Keanu, and the latter for its unrelenting, clinically precise presentation of pathos in a Shakespearean Comedy—Prospero’s Books, Peter Greenaway’s 1991 adaptation of The Tempest, merits viewing for the simplest of reasons: it is one of the most vigorous adaptations of the Bard ever filmed and easily the most competent and compelling version of The Tempest.

Greenaway is a director whose visual exuberance can overwhelm a viewer. I worked in a small campus theater when his oft-disturbing 1989 film The Cook, the Thief, His Wife, and Her Lover first came out. During its week-long run, I noticed two patterns: people often left in the first fifteen minutes; many of those who remained returned to see the film again the next night. Prospero’s Books is not nearly so graphic, but there are still many reasons a casual viewer might dismiss it. Some may be distracted by such superficial elements as the nudity (virtually all the island spirits are naked—and there are a lot of island spirits) or the fact that, as Prospero, Sir John Gielgud delivers 80% of the lines (speaking most of the lines for the other characters through the first half of the film). Then there are the interpretative elements purists might object to: Caliban’s lines (spoken by Prospero) accompanied by modern dance or a tripartite Ariel. And finally, the second half of the film drags somewhat, particularly when viewed on the small screen, where some scenes lose a degree of their sweep and grandeur.

But those who leave the film half-watched or half-attended have done themselves a marked disservice. The marriage of Greenaway’s always extravagant vision with one of Shakespeare’s most mature plays is a remarkable union. In some of his films, Greenaway’s visual palette can seem forced and overly clever—such as his “one controlling color per room” approach in The Cook… or his “gradually ascending numbers” motif in 1987’s Drowning by Numbers—but in the The Tempest, Greenaway’s wildest whims and most bizarre imagery merely soak into the absorbent metaphoric tapestry of the play, adding to the richness without detracting.

Most simply, the story of The Tempest can be viewed on three levels. One can interpret it literally: a bookish ruler is exiled with his daughter by his usurping brother to a remote island. He commands the spirits to his service and eventually has the opportunity to avenge himself on his brother, choosing reconciliation instead. From a more figurative angle, one can interpret the spirits as figments of Prospero’s imagination (and accordingly ascribe varying degrees of reality and explanation to the remainder of the plot). Perhaps the old boy is just a bit loony. Finally, interpreting as pure metaphor, one can view the entire tale as a look into the mind of the writer/artist and into the artistic process itself. These layers of interpretative space allow Greenaway’s most fantastic images ample room to play. Naked spirits? Well, who can say how such inhuman beings would appear to mortal eyes, even those of a magician? Or in the fancy of a senile or mentally unstable man? And couldn’t these images represent the unclothed and often random ideas that exist in a writer’s mind as he or she creates? One of the most absurd images in a panoply of such images further illustrates the example: During the wedding masque for Ferdinand and Miranda, one of the beings presenting gifts is a hooded, naked man with his feet in two buckets of tar. Say what? Yet such an absurdity resonates with a truth about the writing process: For every honed, well-presented trait or detail put onto paper, how many more random, useless, illogical thoughts, details, and even entire characters present themselves to the author only to be quickly dismissed? How many others, even more absurd, flit along the edges, never even gaining form or recognition?

Having Prospero deliver the majority of the lines could easily be regarded as a gimmick, and indeed some reviewers have professed themselves to be distracted by the visuals to an extent where the language is somewhat lost. I found the opposite to be true. With all the lines being delivered in Gielgud’s distinctive voice, I found myself focused on the language in a way that I had never before achieved through reading or attending productions. Indeed, it is Greenaway’s very patience with the delivery of the lines that can make the film seem overlong (especially to American audiences).

Before Prospero’s Books, Greenaway’s visual excess always seemed on the verge of swamping whatever tale he was telling. With The Tempest, Greenaway finally has a story too expansive to overfill; in return, the Bard’s tale benefits from a potent and original retelling. This should not be viewed as an attempt to present the defining interpretation of The Tempest; it is merely meant to be an interpretation. And for all the visual grandeur and excess and distraction in Greenaway’s vision, it is his respect for Shakespeare’s works and language that shines through most clearly. (Respect, not deference.) Like many of Shakespeare’s greatest plays, a production of The Tempest demands certain things from its director: it demands vigor; it demands imagination; it demands respect. Greenaway meets these demands, and for this, he deserves our thanks.